Or: Why I Read (and Love) Genre Fiction

Earlier today, my friend and fellow bibliophile Justine sent me a link to an article about how the internet is ruining our ability to read:

“Humans, [cognitive neuroscientists] warn, seem to be developing digital brains with new circuits for skimming through the torrent of information online. This alternative way of reading is competing with traditional deep reading circuitry developed over several millennia.”

As an avid reader and literacy advocate, I found this fascinating.

I’m just not sure that it’s time to panic yet.

Maybe there’s another culprit.

As you read the article (and please do), you’ll see plenty of anecdotes of people lamenting their inability to read “deeply” or get engaged in a novel:

“After a day of scrolling through the Web and hundreds of e-mails, [Ms. Wolf] sat down one evening to read Hermann Hesse’s “The Glass Bead Game.”

“I’m not kidding: I couldn’t do it,” she said. “It was torture getting through the first page. I couldn’t force myself to slow down so that I wasn’t skimming, picking out key words, organizing my eye movements to generate the most information at the highest speed.””

I’ve felt this way before, and I’m sure you have, too.

It’s important to note that this happened after she put in an eight-plus-hour day of scrolling through the Web and reading hundreds of emails.

Because at that point, she is completely and utterly burned out. Exhausted. Overworked. Of course she’s not going to be able to absorb any new information.

I’m calling Occam’s Razor here. The internet isn’t ruining her brain—her brain is simply exhausted. We’ve all been there, whether it hits us after a long day of work, cramming for a test, or pulling an all-nighter to write a paper.

Reading isn’t dead.

I spent a lot of my life cowed by fear. I decided a long time ago that I’m done with it. So I tend to give alarm-raisers a wide berth and a critical eye.

Often, for every person shouting, “No one’s reading anymore!”, there’s another person clamoring to get his or her next book recommendation from Goodreads, or joining the Slow Fiction movement.

Reading online vs. on paper.

We do read differently online than we do “on paper”, or when we’re reading a book. As a web writer, I write differently online than I do for the novel I’m working on at home.

Online, sentences and paragraphs are brief. Bullet points, headers, and white space are used to facilitate digestion of the main takeaways. We make this change because we’ve learned that online readers tend to skim.

But I think the difference in how we read has less to do with the medium and a whole lot more to do with the message—and the readers’ motives.

When I read online, I skim. I My attention span at that time is probably 15 seconds or less.

Now, a lot of this is due to the fact that many online articles are a waste of time. Many of them repeat something I’ve read before in a similar article, or else they set up a premise that they don’t really fulfill (an incredibly common problem, but that’s a topic for another day).

However, when I’m at home reading something I’m REALLY interested in, I can still get lost for hours.

Not all books are for everyone.

Books can be enjoyed by everyone. But not all books will be enjoyed by everyone.

The article shares the story of one Brandon Ambrose, a “31-year-old Navy financial analyst”:

“His book club recently read “The Interestings,” a best-seller by Meg Wolitzer. When the club met, he realized he had missed a number of the book’s key plot points. It hit him that he had been scanning for information about one particular aspect of the book, just as he might scan for one particular fact on his computer screen, where he spends much of his day.

“When you try to read a novel,” he said, “it’s almost like we’re not built to read them anymore, as bad as that sounds.””

The article makes the assumption that computers have ruined Mr. Ambrose’s brain, and made it impossible for him to enjoy a book.

I’m going to call Occam’s Razor again: perhaps the people who are skimming novels for the highlights simply aren’t interested in those particular novels.

Look. I know The Interestings is a best-seller, but I have ZERO interest in reading it. Apparently, it’s a “panoramic novel about what becomes of early talent, and the roles that art, money, and even envy can play in close friendships.”

Yawn. (No offense to the book’s author or fans.)

It’s extremely likely that Mr. Ambrose, a male Navy financial analyst, would much prefer a Tom Clancy or Ken Follett novel.

Kids these days.

Similarly, kids who have trouble reading classics in school aren’t necessarily bad readers—remember the whole Harry Potter craze?

These kids may simply not be interested in the classics—or perhaps the classics haven’t been properly introduced to them.

I hated English when I was in high school. I hated it because I had to read freaking Tess of the d’Urbervilles instead of the sci-fi genre novels I devoured when I got home.

I hated Tess and her virtue and her stupid whiny incest-baby. I hated Thomas Hardy’s impenetrable, page-long sentences and archaic language that I had to struggle to understand.

I had been handed this behemoth of a novel as a 1990s-era teenager without any instruction on how to appreciate it—or any knowledge of what there was to appreciate within its pages.

I didn’t understand it—the book was completely inaccessible to me.

This is probably a much larger topic for another day, but in order for someone to become engaged with something, they have to want to engage with it. And to want to engage with it, they have to understand its value.

What is the value of the book you’re reading?

For me, the value of sci-fi was obvious. Science fiction:

- expanded my mind,

- showed me adventures I couldn’t have in real life, and

- gave me characters to love like my own friends.

These are values that I discovered on my own, which made them not only important to me but part of me—internal.

The value of Tess was externally commanded, and never explicitly shared with me by my high school English teacher, other than “Read this, take the test, and get an A.”

For today’s skimming book-clubbers, that externally commanded value might be, “Read this, discuss it in that book club you’re obligated to attend instead of hanging out at home watching football, and feel marginally smarter/better about yourself.”

Be intentional about whatever you’re reading.

Today, there are still a lot of classics I don’t like (despite holding a degree in English literature, and having cultivated the appreciation for such).

In fact, I still can’t read Thomas Hardy without wanting to punch someone. (Sadly, I cannot punch Thomas Hardy because he is dead.)

Instead, I’ll intentionally search out one or two classics that interest me per year (right now I’m reading Moby-Dick, which is awesome—but still has a rather intimidating barrier to entry).

Then, I’ll supplement the rest of my year’s reading with genre fiction, because at the end of the day, expanding my mind, enjoying escapism through adventure, and befriending fake characters are still of utmost personal value to me.

Reading isn’t dead.

You need to know that I’m not a cognitive neuroscientist. In fact, I’m not a scientist of any kind. I’m just really, really passionate about books and reading. I’m also really, really opinionated.

At the end of the day, I think we still have a long way to go in understanding people’s motives for reading.

I think that we read differently online because we’ve been trained to do so by crappy web content and the obnoxious ads that our eyes have to weave past.

I think that it’s unreasonable to expect our brains to want to read and absorb information after a full workday of reading articles and responding to hundreds of emails.

I think that if you give the right person the right book, he or she will have no trouble engaging with it, and settling into that “deep reading” state that’s so immensely satisfying.

So make a cup of tea. Turn your phone on silent and hide it in your silverware drawer. Coax your cat into your lap. Open up your book (or turn on your Kindle or iPad). And read.

Because reading’s not dead. Not yet.

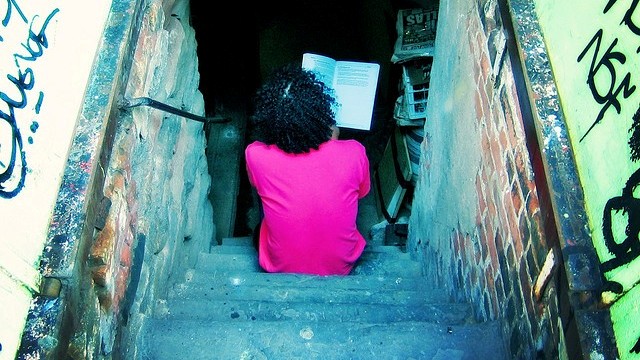

Image via Flickr: “Reading Well” by Mo Riza

Heh. Whiny incest babies. Funny.